By Francis X. Maier

Colorado has dozens of ski resorts. The official count is 41. Vail and Aspen, Telluride and Steamboat Springs soak up most of the attention. But small gems like Wolf Creek and Crested Butte abound. Our family’s favorite, during the 18 years we lived in Denver, was Arapahoe Basin. Located on the Continental Divide, just 105 km from our home, “A-Basin” was easily accessible and a relaxed magnet for locals. It offered some beginner runs, but the place had—and has—few frills and little patience for pretentiousness.

A-Basin attracts the serious skier. The Lenawee Express chairlift drops skiers at 3,797 meters elevation. From there, the more experienced—or the more daring—can ascend to the top of the East Wall, with its double black diamond runs, at over 4,000 meters. Out of prudence or cowardice, I never made the summit. The imprudent can fall 180 meters. But skiing down from Lenawee is already a sacramental experience in itself: the speed, the fierce and thin air, the whisper of the snow under the skis… everything suspends time.

The true glory of A-Basin, however, is the rising sun illuminating the face of the East Wall at dawn: a panorama of bare granite, colossal and majestic. It is inhuman. More than human. And for anyone with eyes and soul, it imposes humility. As God said to Job: “Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth… when the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God shouted for joy?” (Job 38:4-7).

There, on the East Wall, those words still echo in the air.

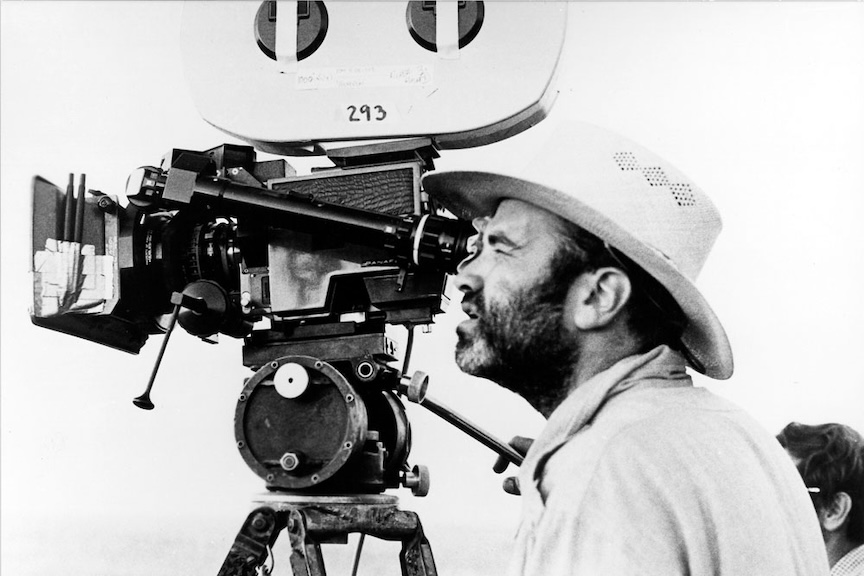

All this lives in my family’s memory. But what awakened it in me recently was a conversation with a good friend. We both love movies. He mentioned his annoyance with overhyped directors like Stanley Kubrick, Francis Ford Coppola, and Terrence Malick. It’s true that Hollywood covers its “geniuses” with as much praise as lava covered Pompeii. But regarding Malick, we disagree. His films have often had a Christian undertone, and two in particular speak powerfully to our present moment.

The first is A Hidden Life (2019), based on the story of Franz Jägerstätter. This Austrian peasant, born out of wedlock in 1907, was raised Catholic but underwent a deeper conversion in the 1930s, amid the rise of Nazism and after his marriage to Franziska, a fervent Catholic.

In 1938 he was the only one in his village to vote against the Anschluss. With the increase in Nazi atrocities and pressure on the Church, he became more vocal. Called up for military service in 1943, he refused to swear loyalty to Hitler, claimed conscientious objection, and offered to serve in a non-combatant role. He was arrested and charged with undermining military morale. In August 1943 he was executed. In 2007, Benedict XVI declared him a martyr, and that same year he was beatified.

Malick captures Jägerstätter’s life and the tenderness of his family with great skill. The decisive scene occurs in prison, when his lawyer tells him that if he signs a recantation, he will be released. Franz asks: “Would I have to swear loyalty to Hitler?” The lawyer replies: “It’s just words. No one takes them seriously.” Jägerstätter responds: “I cannot.” And when he insists: “Sign and you’ll be free,” he replies: “But I am free.”

Because words matter. They reveal and bind the soul. False words poison it. That’s why the philosopher Josef Pieper described much of modern political language as an instrument of violation.

The second film is The Tree of Life (2011), a masterpiece. Those seeking explosions, sex, and car chases will feel baffled. I myself abandoned it twice in the first fifteen minutes. Mistake. The film is loaded with biblical and Christian references: from the title (Genesis, Proverbs, Revelation) to its beginning (Gen 1:2-4; Job 38:4-7) and its ending (Jn 1:5). It requires attention and patience. But every minute is worth it.

It is the story of a successful man (Sean Penn) in a midlife crisis, who remembers his deceased brother and his parents, representatives of two paths: the mother, “the way of grace” (Jessica Chastain: mercy, forgiveness, love) and the father, “the way of nature” (Brad Pitt: ambition, selfishness, conflict).

The redemptive ending, with the protagonist’s slight smile as he finally discovers the beauty around him, is unforgettable. Nor are the mother’s words forgotten: “The only way to be happy is to love. If you don’t love, your life will pass you by. Do good. Be amazed. Have hope.” And the father’s, repentant: “I wanted to be loved because I was great. An important man. [But] I am nothing. Look at the glory around us: the trees, the birds. I lived in shame. I dishonored everything and didn’t notice the glory.”

The lesson, I suppose, is this: we live in a time that manufactures artifices of our life. But God remains. And we need to notice his glory.

About the author:

Francis X. Maier is a senior research fellow in Catholic studies at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. He is the author of True Confessions: Voices of Faith from a Life in the Church.