By Andrew Shivone

Recently I attended a professional baseball game in Texas. The game took place in a completely new stadium, costing several billion dollars, that has all imaginable amenities. It was played under a roof, at a pleasant 21 degrees, and snacks could be ordered from a free app and arrive in less than five minutes.

However, what struck me the most was how difficult it was to watch the game. Except when the ball was in play, the giant screens and speakers were constantly “entertaining” the public or selling some product.

There was not—and I say this literally—a single moment of silence throughout the entire evening. The paused drama of baseball, which can only be enjoyed with attention, was drowned out by a tsunami of noise.

It is curious that all this activity, supposedly designed to generate excitement and participation, had a sedative effect on the crowd. Hardly anyone seemed to be entertained.

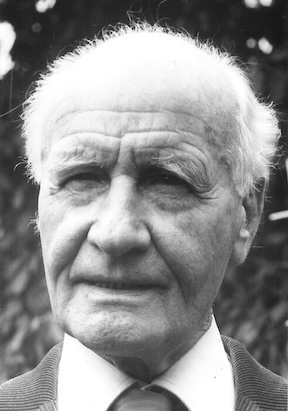

After the game, I recalled a short but illuminating essay by the philosopher Josef Pieper, titled “Learning to See Again”, in his book Only the Lover Sings: Art and Contemplation. There, Pieper points out that the incessant assault of images and noise numbs our sensitivity to reality.

He proposes two remedies that, in my opinion, are especially valuable for Catholic schools today.

First, he proposes that we undertake a personal regimen of abstinence and fasting from the bombardment of noise. The goal here is to keep the “noise of daily banalities” at a distance to open up space for silent and careful observation and reception.

But it is not enough to be silent and passively attentive. For this reason, Pieper adds a second suggestion: the most effective remedy is “to be active in artistic creation, producing visible forms and figures.” He writes that “the simple attempt to create an artistic form forces the artist to look at visible reality with new eyes; it requires authentic and personal observation.”

What Pieper describes here is precisely what Catholic schools should strive to achieve in their classrooms. First, we seek to create a certain tranquility, a peaceful environment in the classrooms and other school spaces, which initially requires some abstinence and self-mastery. But that is only the initial condition for learning. The second is to get the students themselves to create actively: participating in real conversations, singing, drawing an object, or arguing a thesis.

Even if the students do not become composers, nor painters, nor even have to argue in public, these activities are extremely valuable. Because they are not done solely to develop skills or learn a subject, but to learn to be attentive and to care for the reality that surrounds them.

By learning to create, we learn to perceive and attend. We could even say that we learn something of the suffering proper to love.

Let us go a little further than Pieper. The effort to create and know not only helps us to attend to the world and to people, but also to learn to attend to God in prayer.

The habit of study and careful creation bears its highest fruit in loving and contemplative union with God. Certainly, the capacity to do this is a grace, but like every grace, it also acts through and in our own efforts.

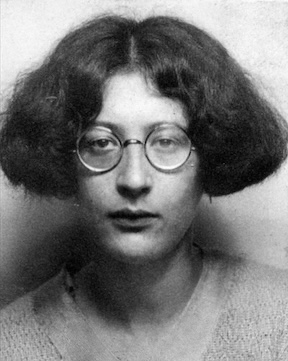

The great Jewish philosopher Simone Weil points this out in her beautiful essay on study and prayer:

If we concentrate our attention on trying to solve a geometry problem, and after an hour we are no closer to the solution than at the beginning, nevertheless, we have advanced every minute in another more mysterious dimension. Without knowing or feeling it, that apparently sterile effort has brought more light to the soul. The result will be discovered one day in prayer. Moreover, it may make itself felt in some part of the intelligence without any relation to mathematics. Perhaps the one who made that failed effort one day will be able to grasp with greater vividness the beauty of a verse by Racine. But it is certain that that effort will bear fruit in prayer. There is no doubt about it.

That is why it is so important that our Catholic schools be places of true creativity and study, and also why Catholic schools must never submit to the tyranny of noisy technology. Above all other tasks, we must cultivate the habit of attention and humility that allows us to sit at the feet of our Savior and attend to Him.

About the author:

Dr. Andrew Shivone is president of the St. Jerome Institute in Washington, D.C. He earned his doctorate in Theology at the Pontifical John Paul II Institute, with a thesis on the philosophy of education and childhood in the thought of the German Thomist Ferdinand Ulrich. He has published articles and translations in Humanum Journal and Communio, and is currently preparing a translation of Ulrich’s book on childhood and education, Der Mensch als Anfang (Man as Beginning).