By Casey Chalk

Consider the following: “In those early times of our American grandfathers and great-grandfathers, two dominant visions loomed over their lives. One was the spiritual design of the national union, which in the Civil War required so much courage and sacrifice to ensure. The other was the continental destiny of the United States, which in the conquest and colonization of the West demanded so much work and love to be fulfilled.”

Courage, sacrifice, work, love: these are not words that are heard very often in contemporary narratives of American history, and certainly not about the expansion to the West. It is much more common to hear about theft, exploitation, racism, and violence.

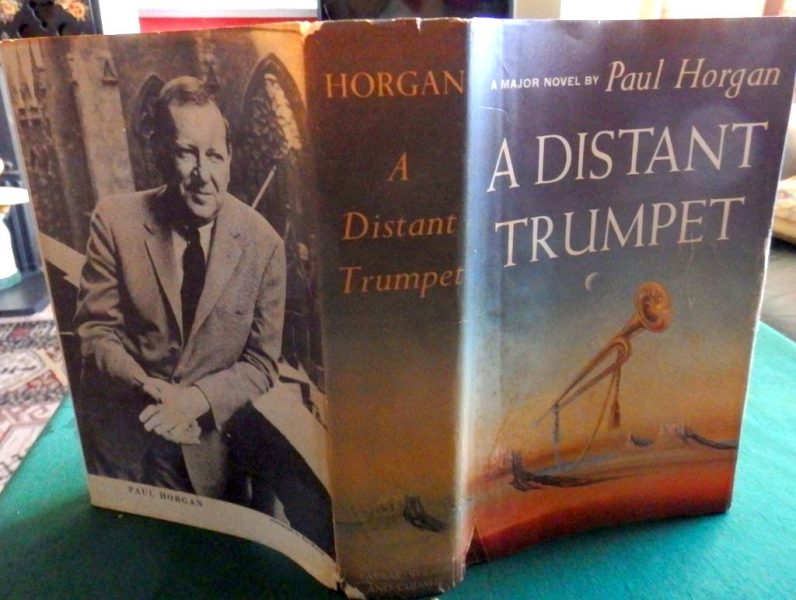

However, that is how Paul Horgan, the Catholic writer and two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, begins his epic novel A Distant Trumpet (1960), a bestseller that recounts the stories of U.S. Army soldiers and their wives, as well as the Apache warriors they faced in the final days of the American frontier. It is a captivating saga that, in its brutal honesty, rivals the best westerns, and in its optimism offers an implicitly Catholic counterpoint to a genre often dominated by nihilism.

In his afterword, Horgan—who was named a papal knight by Pope Pius XII—cites abundant primary and secondary sources: memoirs, official congressional publications on Indian affairs and border issues, compensation claims, military policy and experience records, and reports from the Surgeon General. “This is a historical novel,” he explains, “which means that a period and a scene have been enriched—indeed, largely created—through general references to known circumstances.”

What were those circumstances? Army officers with diverse motivations and competencies, in command of similar soldiers, many of them first-generation immigrants from Western Europe, whose native language was not English. A young idealistic officer is warned: “You must learn that the army is like any other human institution: it contains all kinds of men, capable of any error, just like those outside.”

The soldiers served on an inhospitable and dangerous frontier, far from stable communities, aware that fierce Native warriors roamed the territories freely.

Nevertheless, Horgan shows great knowledge and respect for Apache culture. He praises their reverence for ancestral lands and acknowledges that their warriors possessed an ancient nobility and indomitable courage. That ferocity, however, was sometimes expressed in horrific acts, such as torturing and mutilating soldiers and settlers.

The fear of the Apaches was such that the few women in the military posts—officers’ wives and laundresses—had to learn to shoot, and if they were in danger of being captured, they were instructed to use the bullets on themselves.

However, with a Catholic ethical background, many Anglo-American characters try to treat the Indians as people, not as subhuman savages. Even in circumstances where everything seemed to push them to deny their dignity. (Horgan, who had won a Pulitzer for his biography of Archbishop Jean-Baptiste Lamy, a missionary in New Mexico, was well acquainted with these Anglo-Native tensions).

Horgan does not ignore the mistreatment that the U.S. government and army inflicted on Native peoples. Rather, he shows that there were Americans who respected their counterparts and recognized that their own people were also capable of great evils. As one officer states: “Indian barbarity and cruelty, ingenious and relentless as they are, are nothing more than fragments of humanity’s general capacity for barbarity and cruelty. The Indians do not have a monopoly on those traits; nor can we whites claim virtue and enlightenment exclusively.”

Of course, A Distant Trumpet also contains passages of a darker vision of the West, reminiscent of masterpieces like Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. Two Confederate gentlemen who emigrate to Mexico dreaming of riches and noble titles are murdered by a young American adventurer they had taken in. He, in turn, dies at the hands of Mexican criminals.

But what makes Horgan’s novel unique is its ability to unite the barbarity of the West with moments of hope and humanity. Like a pregnant mother contemplating the new life she will soon bring into the world. The husband, reflecting on her sacrifice and that of the child, feels moved to a greater sense of chivalry. The wife, determined to give birth in the fort despite her husband’s past infidelities, offers an example of forgiveness and virtue absent in modern westerns, which focus on revenge rather than mercy.

A story without any evil would be sweetened and inhuman. But the opposite also distorts reality: even under great suffering, people often choose the good. The newborn baby is baptized on the frontier by the Catholic wife of another officer. The West, Horgan writes, “brought together people from both sides of the War in a new purpose, and to those who went there it offered danger, hope, and a share in heroic creation.”

Before a battle against the Apaches, an officer reflects: “Should a man be as strong to face the knowledge of himself as to impose his power on the world?” That is a much more complex—and frankly Catholic—question than the typical western’s Manichean narratives.

And it is also a very relevant question for our own struggles, when our principles are tested by suffering and evil. “In skirmish or battle everything happens too fast to philosophize in the moment. But if one brings his philosophy with him, everything is shown in its light: the fight, the good, the evil, and the sacrifice appear clearly.”

A sentiment worthy of the Summa.

About the author:

Casey Chalk is the author of The Obscurity of Scripture and The Persecuted. He contributes to Crisis Magazine, The American Conservative and New Oxford Review. He studied history and education at the University of Virginia and earned a master’s in theology at Christendom College.